C/O Berlin shows “Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel,” the first cross-section through the work of the great American photographer ever presented in Germany.

Right when it opened in March, I had the plan to go see the exhibition “On Being an Angel” at C/O Berlin. Then came the pandemic, and the sudden lockdown thwarted my plan.

The abundance of places where the arts reside makes life in a big city so livable.

As things have gradually returned to normal I decided to make up for the shelved plan yesterday. I was excited about finally going to visit a museum again for the first time in months. And my excitement would have hardly been diminished had I known that C/O Berlin actually prefers to call itself an exhibition venue rather than a museum. The abundance of places where the arts reside makes life in a big city so livable. When these places had to shutter in order to slow down the spread, the city suddenly seemed to have lost its soul—and it’s a good feeling to finally have some of it back.

The first picture in the exhibition that captured my attention is quite a blurry one. A naked human body, presumably the artist herself, is crouching through an object that looks like a tombstone with a little window in it. The body is on all fours, segmented by the tombstone, much like in the classic magic trick “sawing a woman in half”. The picture is untitled, created in Boulder, Colorado, dated 1972-5. It’s one of Woodman’s earlier works; she was still a teenager when she took it.

Later I find out that Woodman was a teenager for most of her productive life. She died what the curators call ‘an all too premature death’ at the age of 22. Despite her short lifetime, Woodman left behind some 800 photographic prints—and this number seems to have only grown over the years since her passing: Rosalind Krauss still writes of “five hundred or so photographs” (Krauss 1999, 162) in 1986, Jillian Steinhauer of “some six hundred” (Paris Review 2012), and Anna Backman Rogers of “some 800 photographs” (Backman Rogers 2018, 101).

Woodman’s is the rare case of a prodigy-photographer. She took her first picture at the age of 13 when her father gave her a camera. Later she studied at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with Aaron Siskind, went to Rome through the school’s European Honors Program, spent some time at the MacDowell artists’ colony in New Hampshire, and finally moved to New York where she briefly got involved with fashion photography.

Through the photographic lens, Woodman presents herself as a performance artist, though without any signs of self-staging.

Most of the pictures in the exhibition show the artist herself and pretty much all works presented have something performative to them. The bodies appearing in the pictures ‘play’ the space, they nestle up against objects and environments, peeling themselves out of their surroundings, adopting unusual poses, often in motion, captured as blurs by Woodman’s long exposures. Through the photographic lens, Woodman presents herself as a performance artist, though without any signs of self-staging. The camera is “her only spectator,” as the curators write, but this spectator is certainly no stranger to her. There’s no sign of exhibitionism, no voyeurism, nor shame. Interestingly, I believe I can decipher the word ‘shame’ scribbled on a mirror that appears in the picture series entitled “Charlie the Model”—or does it actually say ‘Charlie’ on that mirror?

Many of Woodman’s notes accompanying the pictures seem noteworthy. She scrawled them on the backsides or on the cardboard mats that her RISD assignments are mounted on (Krauss 1999, 162). The mentioned series features her, naked, together with a male nude model about 30 years her senior who has a round belly. Below one of the pictures, the artist noted: “Charlie has been a model at RISD for 19 years. I guess he knows a lot about being flattened to fit paper.” (Krauss 1999, 165-6). And the caption beneath another one says: “Sometimes things seem very dark. Charlie had a heart attack. I hope things get better for him.”

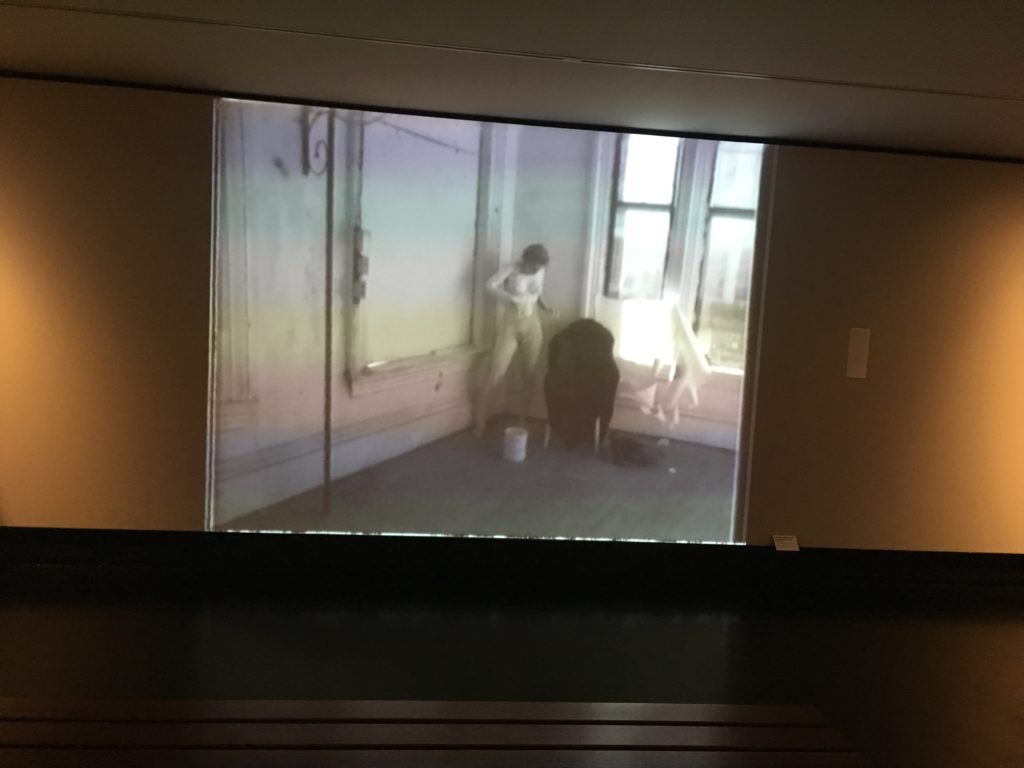

The exhibition also features a selection of videos by Woodman. In one of them, she enters a room, wearing a fur coat and boots, and slowly starts to undress. Once naked, she slathers her body with a substance that first looked to me like white paint (it’s actually flour). Then she lies down on the ground in the graceful posture of a lying sculpture. When she eventually gets up again, there’s an imprint of her body on the ground—with dark shades, more defined than just a silhouette.

An untitled series created in 1980 at the MacDowell Colony suggests assimilations or transformations from human to tree-like shapes—Woodman wears the bark of birch trees around her arms, a dress that mimics the same pattern, and her body adopts tree-like poses. These pictures of a metamorphosis evoke classic motifs, such as Daphne, the nymph who turns into a laurel tree while chased by the god Apollo, or Philemon and Baucis, the couple who are transformed into a pair of trees upon their death.

Another series of the same year bears even clearer references to classic antiquity. Titled “Blueprint for a Temple” it consists of larger than life prints showing the structures of a Greek temple composed of female bodies, reminiscent of caryatids.

These later works appear to be a crystallization of what’s implicit in the earlier pieces. Woodman’s pictures show the human body—especially the female body—not simply as an object in space, but as an element of space. Her bodies are structural elements of geometry, they segment space as much as they are segmented by it. And at the same time, they raise the question: what’s on the other side of space, what’s on the other side of the body?

On January 19, 1981, Francesca Woodman threw her body out of a Manhattan window. “Simply the other side” were the last words she wrote in her journal.

—

Rosalind Krauss: Francesca Woodman. Problem Sets [1986]. In: Bachelors. Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 1999.

Anna Backman Rogers: ‘Not Because My Heart is Gone.’ In: Female Agency and Documentary Strategies: Subjectivities, Identity and Activism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Now I am curious about Francesca Woodmann. I’ve never heard of her.